IEEE 754

Systems in Rust

Announcements

- Welcome to Systems in Rust

- Action Items:

- “SHA-512” is due on next Friday

- Lecture on numbers, inspired by the lab, while we wait.

Today

- Understand precision through the lens of floats.

- Understand the basics of floats

- Understand the language of floats

- Get a feel for when further investigation is required

Citation

- Yoinked

- url

- Author John Farrier, Booz Allen Hamilton

Mission Statement

- I’m a normal person.

- I think

5/2is2.5or perhaps 2½.

- I think

- I’m a scientist.

- I’m solving “Black-Scholes”

- Does anyone know what this is doing? \[ d_2 = d_1 - \sigma\sqrt{T - t} = \frac{1}{\sigma\sqrt{T - t}}\left[\ln\left(\frac{S_t}{K}\right) + \left(r - q - \frac{1}{2}\sigma^2\right)(T - t)\right] \]

Common Fallacies

- “Floating point numbers are numbers”

max(count())Pinocchios

- “It’s floating point error”

- “All floating point involves magical rounding errors”

- “Linux and Windows handle floats differently”

- “Floating point represents an interval value near the actual value”

Common Fallacies 2.0

Anatomy of IEEE Floats

IEEE Float Specification

- IEEE 754-1985, IEEE 854-1987, IEEE 754-2008

- These are paywalled.

- Those are years.

- Provide for portable, provably consistent math

- Consistent, not correct.

Assurances

- Ensure some significant mathematical identities hold true:

- \(x + y = y + x\)

- Symmetry of addition

- \(x + 0 = x\)

- Additive identity

- \(x = y \implies x - y = 0\)

- Identity under subtraction

- \(x + y = y + x\)

Assurances 2.0

\[ \frac{x}{\sqrt{x^2+y^2}} \leq 1 \]

- What is missing?

IEEE Float Specification

- Ensure every floating point number is unique

- Ensure every floating point number has an opposite

- Zero is a special case because of this

- Specifies algorithms for addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and square-root

- Not really operations/relations! They are algorithms.

Aside: Scientific Notation

- In scientific notation, nonzero numbers are written in the form

\[a \times 10^b\]

Aside: Explanation

- In scientific notation, nonzero numbers are written in the form

\[a \times 10^b\]

- \(a\) (the coefficient or mantissa) is a number greater than or equal to 1 and less than 10 (\(1 \le |a| < 10\)).

- \(10\) is the base.

- \(b\) (the exponent) is an integer.

Aside: Physical Examples

Speed of light: The speed of light in a vacuum is approximately \(300,000,000 \text{ m/s}\) \[ 3 \times 10^8 \text{ m/s} \]

Mass of an electron: The mass of an electron is approximately \(0.00000000000000000000000000091093837 \text{ g}\). \[ 9.1093837 \times 10^{-28} \text{ g} \]

Aside: Economic Examples

- We can use social science numbers.

- Labor Market Outcomes of College Graduates by Major

- Computer Science majors in 2023 have a $80,000 median wage “early career”

- \(8.0000 \times 10^4\)

- And 6.1% unemployment

- \(6.1 \times 10^{-2}\)

IEEE Layout

- An approximation using scientific notation

- \(x = -1^s \times 2^e \times 1.m\)

- \(x = -1^{\text{sign bit}} \times \text{base} 2^{\text{exponent}} \times 1.\text{mantissa}\)

- Where the mantissa is the technical term for the the digits after the decimal point.

With Binary

- \(x = -0b1^{\text{0b0}} \times 0b10^{\text{0b10000000}} \times 0b1.10010010000111111011011\)

- Express in memory as the concatenation:

0b0to0b10000000to0b1001001000011111101101101000000010010010000111111011011

Singles and Doubles

- 32 - bits = 1 sign bit + 8 exponent bits + 23 mantissa bits

0b0to0b10000000to0b10010010000111111011011

- 64 - bits = 1 sign bit + 12 exponent bits + 52 mantissa bits

Understanding check

- What is the probability a real number \(a \in \mathbb{R}\) has an exact float representation?

- What is the probability an integer \(n \in \mathbb{Z}\) has an exact float representation?

- What is the probability a course number \(n < 600\) has an exact float representation?

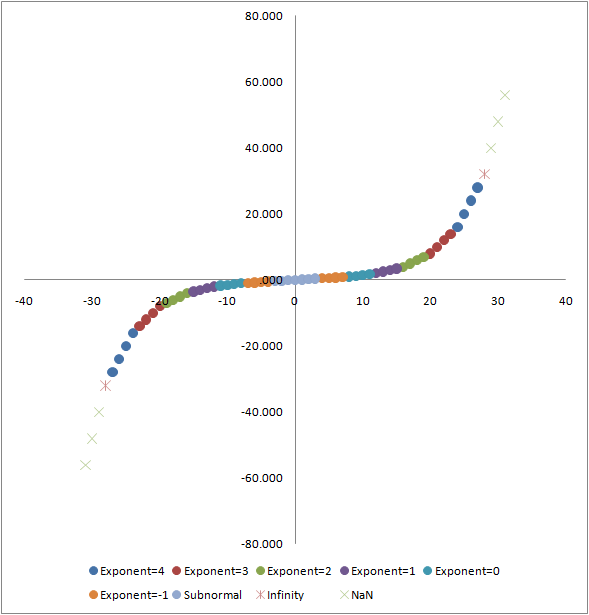

Special Floats - NaN

- Divide by Zero

- 1 / 0

- Not a Number (NaN)

Special Floats - inf

- Signed Infinity

- Overflow protection

Infinity is signed

- We can get negative infinity through a variety of means.

- We note that this suppresses the overflow error use

() - In some languages this is not ever regarded as an overflow error, like Julia (where we have to use larger powers due to the f64 default)

Signed Zero

- Signed Zero

- Underflow protection, preserves sign

- 0 =− 0

- Works in base Python (e.g. don’t need NumPy).

- Couldn’t get it to work in Julia actually (went to -inf or NaN)

Simple Example

- Floating point is great because it will work exactly how you expect.

- More or less.

Simple Example

- We shouldn’t be suprised by this!

>>> _ = [print(f"{f32(i/10):1.100}") for i in range(1,4)]

0.100000001490116119384765625

0.20000000298023223876953125

0.300000011920928955078125

>>> _ = [print(f"{f64(i/10):1.100}") for i in range(1,4)]

0.1000000000000000055511151231257827021181583404541015625

0.200000000000000011102230246251565404236316680908203125

0.299999999999999988897769753748434595763683319091796875Storage of 1.

- \(x = -1^s \times 2^e \times 1.m\)

- \(x = -1^{\text{sign bit}} \times \text{base} 2^{\text{exponent}} \times 1.\text{mantissa}\)

- \(x = -1^{\text{sign bit}} \times \text{base} 2^{\text{exponent}} \times 1 + \text{mantissa} \times \frac{1}{2^n}\)

- \(1 = -1^0 \times 2^0 \times (1 + 0 \times \frac{1}{2^n}\)

- So each of the sign bit, the base, and the mantissa are zero.

- I should note I was unable to reproduce this in Rust or C.

- I’m not really a floating pointer.

Except…

- This is actually a little bit fake.

$ cat src/main.rs

fn main() {

let x:f32 = 1.0;

println!("{:032b}", x.to_bits());

}

$ cargo run

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.00s

Running `target/debug/bits`

00111111100000000000000000000000- What is that?

Shift 127

- The IEEE 754 binary format specifies a hardware implementation of such that the exponent, be it positive or negative, in binary formats is stored as an unsigned number that has a fixed “bias” added to it.

- In the case of 32 bit floats, the bias is 127.

Breakdown

- Take the following:

- That is:

- Sign bit of

0 - Exponent of

01111111- All zeroes and all ones are reserved for

NaN,inf, etc.

- All zeroes and all ones are reserved for

- Mantissa of 23 zeroes.

- Sign bit of

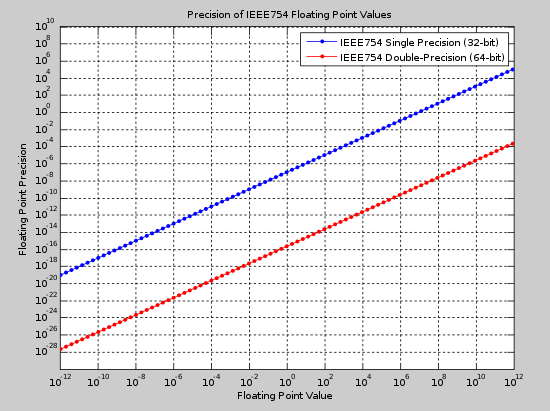

How precise?

- I have referred to

f32as having “32 bits of precision”. - How much precision is that?

- Well, let’s set the least significant bit of the mantissa to one.

“Epsilon”

- What do we get?

$ cargo run

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.00s

Running `target/debug/bits`

00111111100000000000000000000001

1.00000011920928955078125000000000- We refer to this value (less one) as machine epsilon, or perhaps \(\varepsilon\).

- The difference between 1.0 and the next available floating point number.

- Much lower, of course, with double and quad precision.

Easier: “Sig figs”

| Format | Sign | Exp. | Mant. | Bits | Bias | Prec. | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Half | 1 | 5 | 10 | 16 | 15 | 11 | 3-4 |

| Single | 1 | 8 | 23 | 32 | 127 | 24 | 6-9 |

| Double | 1 | 11 | 52 | 64 | 1023 | 53 | 15-17 |

| Quad | 1 | 15 | 112 | 128 | 16383 | 113 | 33-36 |

Sig figs

- IEEE 754 was intended for scientific computing

- That is, not systems computing, software etc.

- Useful to us to think about information and how bits work.

Small Values

- For 32-bit floats, the minimum base 10 exponent is -36.

- How is \(1.0 \times 10^{-37}\) represented?

Test it

- Write a simple test…

src/main.rs

- Results are as expected.

“Denormalized Number”

- Numbers that have a zero exponent

- Required when the exponent is below the minimum exponent

- Helps prevent underflow

- Generally speaking, if you are using one these, the math is about to get wronger than you’d think.

- The good (???) language C++ provides a

std::nextafterfor which Rust crates exist.

Floating Point Precision

- Representation is not uniform between numbers

- Most precision lies between 0.0 and 0.1

- Precision falls away

Visually

Floating Point Precision

The number of floats from 0.0

- … to 0.1 = 1,036,831,949

- … to 0.2 = 8,388,608

- … to 0.4 = 8,388,608

- … to 0.8 = 8,388,608

- … to 1.6 = 8,388,608

- … to 3.2 = 8,388,608

Errors in Floating Point

- Storage of \(\pi\)

>>> from numpy import pi as pi

>>> # copy paste Wolfram|Alpha

>>> '3.14159265358979323846264338327950288419716939937510582097494459230781640628'

'3.14159265358979323846264338327950288419716939937510582097494459230781640628'

>>> f'{pi:1.100}'

'3.141592653589793115997963468544185161590576171875'- They differ fairly early on!

Measuring Error: “Ulps”

- Units in Last Place

Haskell

- Usually ULP is taught using Haskell.

- I’ll translate to .py/.rs

Generators

- By convention we check number theoretic results with lazily evaluated generator expressions in Python.

- The following generators all powers of two for a which adding one does not change the value within Python floating points.

Iterators

- Rust doesn’t require iterators, supporting the infinite iterator by default using

unwrap.

let x = (0..).find(|&i| f64::powi(2.0, i) + 1.0 == f64::powi(2.0, i)).unwrap();

let base = f64::powi(2.0, x);

// Prints the result (2^53 = 9007199254740992.0)

println!("2.0 ** x + 0.0 = {:.1}", base);

println!("2.0 ** x + 1.0 = {:.1}", base + 1.0);- I haven’t used

findbefore, this is an LLM donation to our knowledge base. - By the way, that is basically

2 ** 53and there are 52 bits of mantissa precision.

On “Ulps”

- We can measure error using ULPs.

The gap between the two floating-point numbers nearest to x, even if x is one of )them.

Rounding

- We have some guarantees:

- IEEE 754 requires that that elementary arithmetic operations are correctly rounded to within 0.5 ulps

- Transcendental functions are generally rounded to between 0.5 and 1.0 ulps

- Transcendental as in \(\pi\) or \(e\)

- ~9 ulps

Relative Error

- The difference between the “real” number and the approximated number, divided by the “real” number.

- So for

piinf32, around \(2.9 \times 10^{-8}\)

Rounding Error

- Induced by approximating an infinite range of numbers into a finite number of bits

- Rounding is:

- Towards the nearest

- Towards zero

- Towards positive infinity (round up)

- Towards negative infinity (round down)

Rounding Error

- What about rounding the half-way case? (i.e. 0.5)

- Round Up vs. Round Even

- Correct Rounding:

- Basic operations (add, subtract, multiply, divide, sqrt) should return the number nearest the mathematical result.

- If there is a tie, round to the number with an even mantissa

Implementation

- “Guard Bit”, “Round Bit”, “Sticky Bit”

- Only used while doing calculations

- Not stored in the float itself

- The mantissa is shifted in calculations to align radix

- The guard bits and round bits are extra precision

- The sticky bit is an OR of anything that shifts through it

Special bits

- “Guard Bit”, “Round Bit”, “Sticky Bit”

- [G][R][S]

- [0][-][-] - Round Down (do nothing)

- [1][0][0] - Round Up if the mantissa LSB is 1

- [1][0][1] - Round Up

- [1][1][0] - Round Up

- [1][1][1] - Round Up

Significance Error

- Compute the Area of a Triangle given side lengths

- Hero(n)’s Formula:

- Take \(s = \frac{1}{2}(a + b + c)\)

- Then \(\sqrt{s(s-a)(s-b)(s-c)}\)

- Kahan’s Algorithm:

- Take \(((a, b, c) | a \leq b \leq c)\)

- Then \(\sqrt{\frac{(x + (y + z)) \times (z - (x - y)) \times (z + (x - y)) \times (x + (y - z))}{4}}\)

Write them

src/lib.rs

fn heron(a:f32, b:f32, c:f32) -> f32 {

let s = (a + b + c)/2.0_f32;

return (s * (s - a) * (s - b) * (s - c)).sqrt();

}

fn kahan(a:f32, b:f32, c:f32) -> f32 {

let mut s = vec![a,b,c];

s.sort_by(|a, b| a.partial_cmp(b).unwrap()); // "partial"? Why not `.sort`?

let mut prod = s[0] + s[1] + s[2];

prod *= s[2] - (s[0] - s[1]);

prod *= s[2] + (s[0] - s[1]);

prod *= s[0] + (s[1] - s[2]);

return prod.sqrt() / 4.0;

}Test them

src/main.rs

- Oh what’s that?

[src/main.rs:21:5] heron(3.0,4.0,5.0) = 6.0

[src/main.rs:22:5] kahan(3.0,4.0,5.0) = 6.0

[src/main.rs:25:5] heron(a,a,c) = 781.25006

[src/main.rs:26:5] kahan(a,a,c) = 500.0- Using

f64(vsf32) we get 499.9999999999994

Significance Error

- Use Stable Algorithms

- Keep big numbers with big numbers, little numbers with little numbers.

- Parentheses can help

- The compiler won’t re-arrange your math if it cannot prove it would yield the same!

- E.g. you can’t use

<in Rust as you may provide aNaN.

- E.g. you can’t use

Significance Error – Don’t floats?

- Use integers

- Very fast

- Trade more precision for less range

- Only input/output may be impacted by floating point conversions

- Financial applications represent dollars as only cents or tenth’s of cents

Significance Error – Don’t floats?

- Use a math library

- Slower

- Define your own level of accuracy

- Usually GMP or hardware specific.

Significance Error – Don’t floats?

- Execute symbolically

- Slowest

- Arbitrary accuracy

- Round only at output

Significance Error – Don’t floats?

- Write your own library?

- Use vectors of bits or bytes.

- Write your own arithmetic operations.

- Test and debug your own implemention.

- Coming soon to a homework near you!

Algebraic Assumption Error

- Distributive Rule does not apply:

- \(a = x \times y - x \times z \nRightarrow a = x (y - z)\)

- Associative Rule does not apply: 𝑥 + 𝑦 +𝑧 ≠ 𝑥 +𝑦 +𝑧

- \(a = x + (y + z) \nRightarrow a = (x + y) + z\)

- Cannot interchange division and multiplication:

- \(a = \frac{x}{10.0} \nRightarrow a = x \times 0.1\)

Distribution

Association

Interchange

- Check last digit

Floating Point Exceptions

| IEEE 754 Exception | Result when traps disabled | Argument to trap handler |

|---|---|---|

| overflow | \(\pm \infty\) or \(\pm x_{\text{max}}\) | \(\text{round}(x 2^{-a})\) |

| underflow | \(0, \pm 2^{\text{min}}\) or denormalized | \(\text{round}(x 2^{a})\) |

| divide by zero | \(\pm \infty\) | invalid operation |

| invalid | \(\text{NaN}\) | invalid operation |

| inexact | \(\text{round}(x)\) | \(\text{round}(x)\) |

But Wait! There’s More!

- Binary to Decimal Conversion Error

- Summation Error

- Propagation Error

- Underflow, Overflow

- Type Narrowing/Widening Rules

Testing

- Design for Numerical Stability

- Perform Meaningful Testing

- Document assumptions

- Track sources of approximation

- Quantify goodness

- Well conditioned algorithms

- Backward error analysis

- Are the outputs identical for slightly modified inputs?

Today

- Understand precision through the lens of floats.

- Understand the basics of floats

- Understand the language of floats

- Get a feel for when further investigation is required